California’s farmworkers, their families, and the clinicians who care for them breathed a collective sigh of relief when the governor’s office issued a statewide ban in May on the use of the neurotoxic pesticide chlorpyrifos. It could not have come soon enough in places like the San Joaquin Valley, where chlorpyrifos use spikes this time of year primarily on citrus and nut crops.

Chlorpyrifos is in a class of organophosphates chemically similar to a nerve gas developed by Nazi Germany before World War II, and is linked to permanent brain damage in young children. Its heavy use has often left traces in drinking water sources, and a 2012 study by the University of California, Berkeley, found that 87% of umbilical cord blood samples tested from newborn babies contained detectable levels of the pesticide. Farmworkers and their families who live in California’s agricultural communities are on the front lines of exposure to this toxic pesticide, but it can also be found in residue on produce that is exported across the country.

Pregnant women who live near farms that use chlorpyrifos experience an increased risk of having a child with autism. Low to moderate levels of chlorpyrifos exposure during pregnancy are also linked to lower IQs and memory problems, according to researchers. Studies have further raised concerns about decreased lung function and reduced fertility.

Other states are following suit with bills introduced in New York, Oregon, Maryland, and Connecticut, but the ban has particular significance in California, the nation’s largest agricultural economy, where close to a million pounds of the toxic pesticide are used annually.

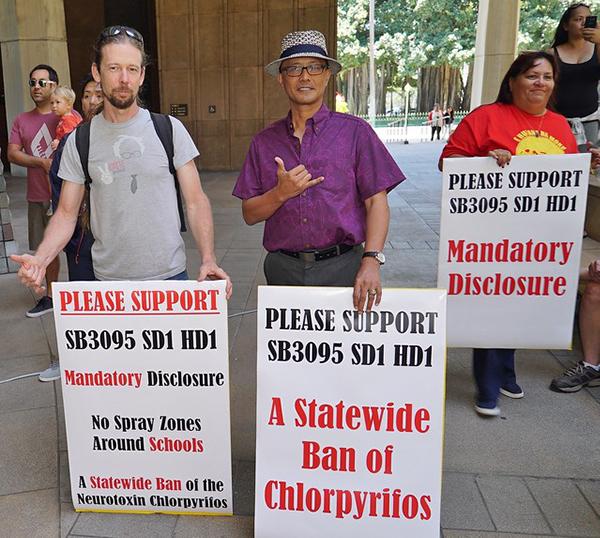

developmental delays in children, in June of 2018 (Hawaii Senate)

A federal nationwide ban of the pesticide was recommended by EPA during the Obama administration, but President Trump’s first pick for EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt, rejected the science and walked back those efforts in 2017.

The continued use of this dangerous chemical on our nation’s food supply underscores the importance of regulation and action – regulation by our federal and state governments and action in the institutional marketplace.

When health care and other sectors expand their purchases of certified organic food, they help transform markets and production practices, making organic foods more affordable and available to the communities they serve.

Hospitals across the country are increasingly purchasing more organic food, supporting farmers and ranchers who are using organic production methods, and those who want to transition to organic.

Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, a Sutter Health facility located in Burlingame, Calif., has prioritized purchasing organic produce whenever possible. They are currently focused on organic sourcing of the items listed on the Environmental Working Group’s ‘Dirty Dozen’ list for 2019, but their long-term goal is to transition their purchases to 100% organic produce.

Four families ate an all-organic diet for one week – and levels of all detected pesticides dropped by 95 percent.

Organic production practices are an important “upstream” investment in public and environmental health. An organic diet rapidly and dramatically reduces a person’s exposure to pesticides, according to a recent study.

When you consider that the health of millions of children and families across the country will be impacted by these purchasing decisions, the right choice should be an easy choice.