Eboni Neal Cochran has a quiet determination that has defined her two-decade fight against industrial pollution in her community. As the co-director of Rubbertown Emergency ACTion (REACT), Cochran has been awarded the prestigious Environmental Health Hero Award from Health Care Without Harm, recognizing her persistent advocacy for the people who live and suffer in the shadow of Louisville's chemical corridor.

"This recognition confirms I'm going in the right direction," Cochran says with measured pride. "But more importantly, it provides another opportunity for people to learn about the issues that plague communities impacted by environmental injustice – like here in Louisville. That's what really makes it meaningful to me."

The Environmental Health Hero Award recognizes an individual or group whose work has deepened our respect for and understanding of the connection between human and environmental health. This highest honor granted annually by Health Care Without Harm recognizes passionate and persistent leaders whose efforts have left a positive impact on the health of the people and communities they serve, whose words and deeds inspire and empower others to act, and whose contributions are advancing our shared work toward environmental health and justice.

Cochran received the Environmental Health Hero award on May 8 during Health Care Without Harm and Practice Greenhealth’s annual CleanMed conference.

We spoke with Cochran about her historical fight for environmental justice in her community and about how health care leaders can tip the scales toward health and safety.

Eboni Cochran’s acceptance speech after receiving the Environmental Health Hero Award

Environmental justice starts with health care

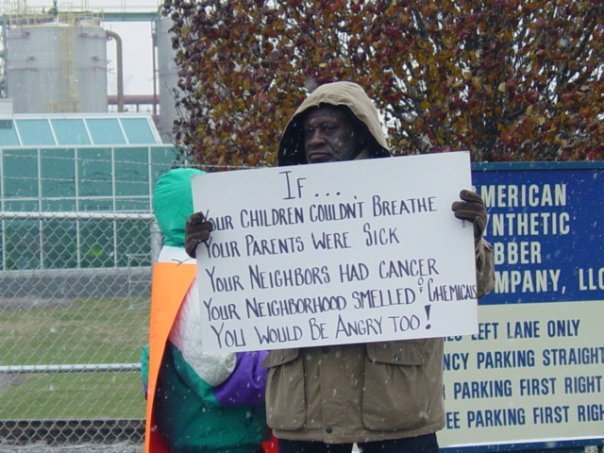

Cochran's battleground is Rubbertown, an industrial area home to 11 large chemical manufacturing facilities and dozens of smaller operations. For generations, these plants have released harmful chemicals into the air, water, and soil in West Louisville, where nearly 60% of residents are people of color and more than 45% live below the poverty line.

A 2004 University of Louisville study confirmed what residents had long suspected: Rubbertown's air quality was the worst in the city, with dangerous levels of known carcinogens like benzene and 1,3-butadiene. The toxic exposure has led to elevated rates of cancer and other illnesses.

According to a 2013 study, people in the zip codes near Rubbertown are nearly 35% more likely to develop lung cancer and 31% more likely to be diagnosed with colorectal cancer than those in the other zip codes. More than 30% of West Louisville residents live with a symptom or illness caused by outdoor air pollution.

Cohran has been working with REACT since 2003, working with community members, educating decision makers, and pushing for reduced exposure to toxic chemicals.

"These chemicals wreak havoc on the body," Cochran explains. "From the nervous system to the reproductive system – it's not just a lack of personal responsibility, which is the messaging that people often fall for. Part of the problem is that there is no requirement for medical students to learn about environmental injustice and how that impacts their patients, and how people become their patients."

of

Smoke stacks in Rubbertown. (Eboni Cochran)

"Rubbertown"

Hear from the people who live in West Louisville about their community's fight for a clean and healthy environment in this 2016 documentary that features Cochran.

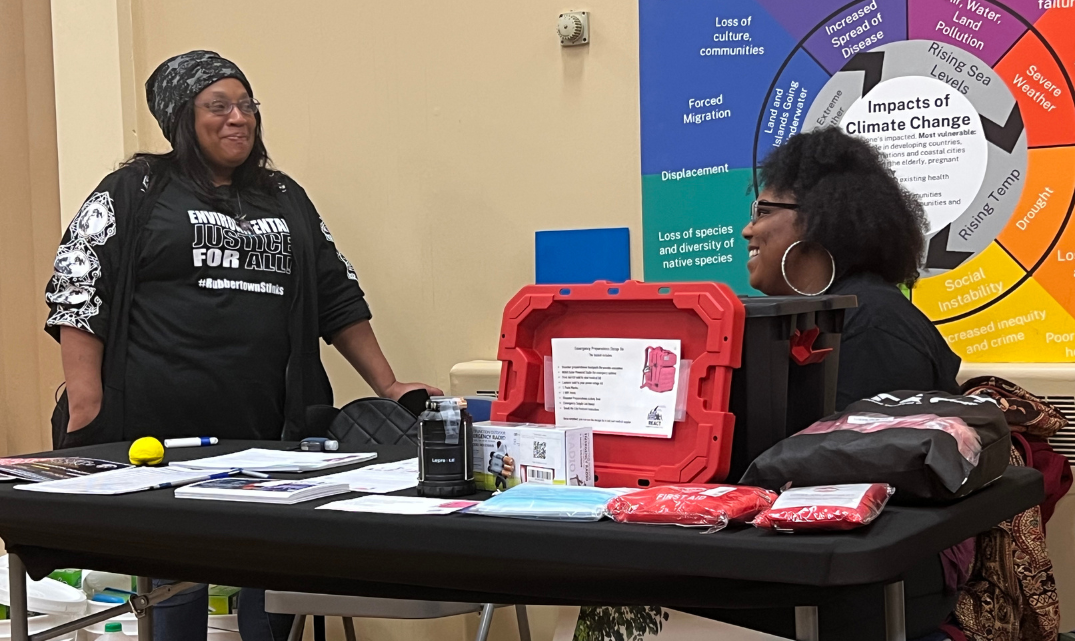

Engaging the community

As our conversation turns to how health care organizations can better support environmental justice, Cochran becomes particularly animated. She points to a new hospital in West Louisville – the first in over 100 years – as both a victory and a missed opportunity.

"When they were talking about building it, one of the things I said at every stakeholders meeting was, 'What sort of materials are you building this hospital with? Are you looking into materials that don't offgas?'"

She sees potential for the hospital to address community health issues directly related to environmental exposure, like elevated blood lead levels.

Cochran explains how the blood lead levels in Rubbertown are more elevated than elsewhere in the city. “We need to be testing children, and if they show high lead levels, testing their parents as well.”

An organized effort through the school system and community testing at the new hospital could make sure no children are left behind. Cochran has personally seen this happen.

“A lot of these children are falling through the cracks. I used to be an assistant in a classroom, and there was a third grader. He was so smart, he was so energetic, but he couldn't read. Not only could he not read, but he could not write the letter H, which I thought was super strange. I'm looking around, wondering, ‘Doesn't anybody else think this is strange?’ Fast forward to the end of the year. They tested his younger brother, who ended up having high lead levels, and when they tested the boy, he had high lead levels, too. But it took the entire school year for them to figure it out.”

Even low levels of lead can lead to learning and behavior problems, and higher levels can result in numerous digestive problems, joint pain and weakness, headaches, and poor growth. Lead poisoning is preventable with widespread testing.

"Health care representatives should go into communities and see the people who are doing the organizing and living in impacted communities as the experts that they are," she advises. "Just because someone has multiple degrees, it doesn't outweigh the lived experience of those who are actually being impacted."

Cochran says nurturing relationships with community members can help heal historic distrust of doctors and the health sector.

“I've been thinking about the challenge of engaging the community. They aren’t often ready to fight when they realize that the change is not going to come immediately. And we also run into folks who, off the bat, don't want to engage because they feel helpless and hopeless. And really, you can't blame them. Because it's difficult to think that anything is going to change when you have not felt tangible change over the decades – when you've been dumped on by chemical facilities in other industries.

Part of the issue, as well, is that the powers that be try to put forth solutions without input from impacted communities. And when you don't engage impacted communities and allow them to help create the plans and the solutions, there's always going to be a gap between what is done and what is needed.”

How health care leaders can improve the regulatory landscape

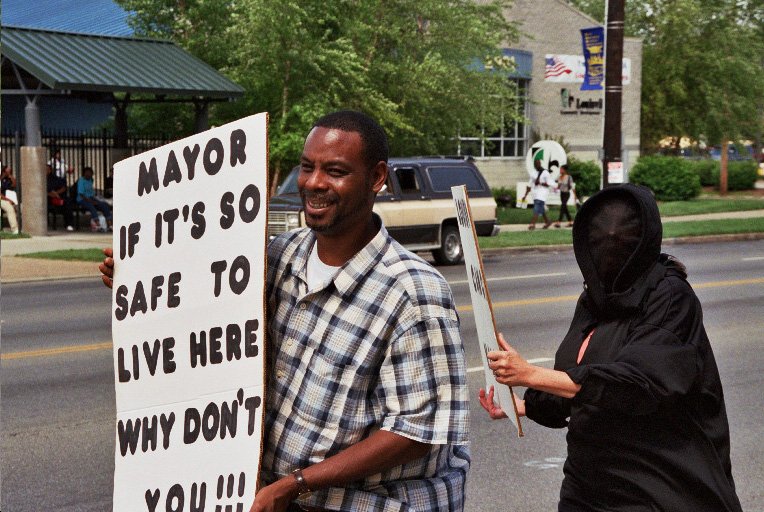

Cochran speaks candidly about the obstacles facing community advocates: the deep pockets of industry, regulatory agencies that seem "in cahoots" with polluters, and legislators who lack the courage to stand with residents.

"While we have to take off work and lose money to attend important meetings and hearings, industry consultants are in the meeting, getting paid," she points out. “You know, it's difficult to remain engaged when you have to sacrifice your livelihood, and they don't.

Our Air Pollution Control District has local authority over our air toxics here in Louisville, and they have the power to make more stringent laws than the federal government. But instead of using that authority to make the regulations stronger, in recent years, they've been aligning with weaker federal regulations. It's such a missed opportunity, and it makes you wonder why. And then you have the legislators who don't have the courage to stand with residents, or those who see you as expendable and industry as priority.”

Cohran says there are several solutions that would help hold companies accountable. But she suspects the bigger issue is that this city does not have much interest in doing so – or enough accountability in place.

“We bring the solutions, and there's no action, and there's pushback. The mayor is always touting safety as a priority, but sees increased policing as the only safety measure [worth implementing] excluding the fact that these industries catch on fire and blow up from time to time. It just makes no sense, other than maybe it's that they see us as expendable.”

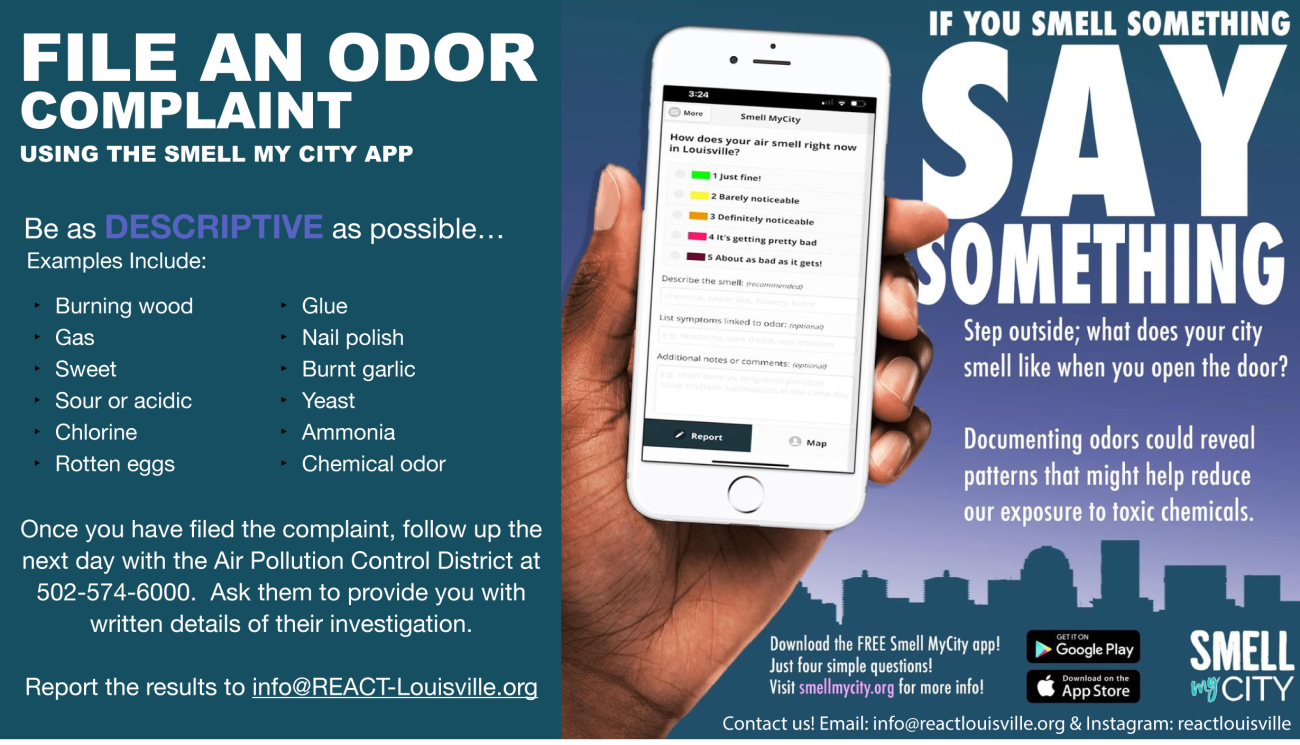

REACT is currently advocating for one small but significant change to the operating procedures by compliance officers at the Air Pollution Control District. Right now, all the compliance officers work the first shift, but many of the violations residents witness happen after the regulatory agency closes for the day. REACT and its allies are asking the mayor and Metro Council to fund additional compliance officers for the second and third shifts, and one stationed in the Park DuValle neighborhood at a police substation. Park DuValle is plagued with odors and is near chemical facilities. This way, when residents need to alert the district of an odor or other sign that could indicate toxic chemical exposure, a compliance officer would be on call when and where they were needed.

“We believe that if the industry runs 24 hours a day, there should be compliance coverage 24 hours a day. Period.”

Cochran urges medical professionals to use their privileged voices during regulatory comment periods:

“We need health care providers and health care facilities to write comments and send them to the EPA or the local Air Pollution Control District, because in the eyes of those decision-makers, medical professionals, what they say holds more weight than those of us who are directly impacted. They sometimes don't see us as a legitimate voice, but they will see the medical professionals as a legitimate voice, and I think if they use their voices in that way, it could be very impactful.”

of

The power of the right question

Cochran's advocacy work is characterized by a sharp intellect and an uncanny ability to ask precisely the right question at precisely the right moment – a skill she credits to her father's persistent advice.

She recounts one of her favorite stories, sitting in a meeting with American Synthetic Rubber Company executives who boasted of reducing their emissions of 1,3-butadiene by 99.7%.

"I started asking myself, '99.7%, what am I doing here if they've reduced the chemical by that much?'" Cochran recalls. Then she remembered her father's words: "The most important thing to know is what question to ask."

So she asked: "What does the other 0.3% represent?"

The answer: 100,000 pounds of a known carcinogen still being released annually into her community's air.

"In that moment, I knew that I still needed to be in that room," she says. "99.7% is nothing when the emissions start out so high."

This advice continues to serve her well.

More recently, Cochran and her colleagues have been monitoring the illegal activities of a Louisville wood processing plant, Anderson Wood. On two occasions, she filmed wood dust and chips expelled by the plant over a fence line and into the community – an action prohibited by city regulations.

“After reading the investigative report from the regulatory agency and realizing that they had not issued a notice of violation, I was confused and puzzled. I mulled over it for a couple of days and finally came to my question: Were they prohibited from using our evidence to issue notices of violation?”

The Air Pollution Control District responded with an answer that Cochran found evasive, claiming, “Their standard practice was that they would not issue a notice of violation without corroborative observation from their compliance officer.”

After confirming with a local environmental attorney, Cochran saw between the lines, “They never said they were prohibited from issuing the notice, they just said they would not do it without their compliance officer being there.” Long story short: The Air Pollution Control District was not prohibited from using the video footage.

REACT started gearing up to do a campaign to call them out. But unfortunately, the Kentucky legislature passed a bill that affects the types of tools that regulatory agencies can use for enforcement action, halting their efforts.

While in this case, REACT was too late to make a difference, Cochran felt reassured by her methodology.

“When a regulatory agency is evasive in its statements, you really do have to know what to ask. It's so important.”

Maintaining health & wellness as an activist

Perhaps most poignantly, Cochran discusses the personal toll of environmental justice work – a dimension often overlooked.

"This work places a burden on activists, their families, and their loved ones," she says. "It's really the equivalent of a full-time job, but there's no pay, and the hours are all over the place."

As a homeschooling mother of one (who also has three adult bonus children and six grandchildren), Cochran has been intentional about protecting her son's childhood from the weight of her advocacy.

"I've been really intentional about not incorporating a lot of the environmental justice stuff that I deal with into our homeschool because it can be super depressing," she explains. "I really wanted him to just enjoy his childhood without wondering if his genes were going to mutate because he was exposed to a mutagen.

I've also had conversations with so many adults who kind of resent the fact that their parents were fighting for the community and not giving them what they needed. So I try to make sure that we have lots of family time.

I think people who do this work have to be intentional about finding joy in everyday life, especially because the work deals with continued issues and impacts that result in suffering and death.”

Small victories, persistent advocacy

When asked about her proudest achievements, Cochran's perspective is grounded in the realities of environmental justice work.

"The wins are not your typical wins," she explains. "It's not going to be every day that you shut down a chemical plant. It's not going to be every day that you convince the EPA to ban a chemical."

Yet she lights up recalling how her community successfully blocked two proposed methane plants from being sited in West Louisville.

"Never before in my years of doing the work had I seen so many individuals showing up to make their voices heard," she says. "They were not going to stand for one more industry being sited in West Louisville.

Between those individuals, several organizations, and the state legislator, all of us were able to stop those methane plants from being sited in West Louisville. Wins don't get much clearer than that, especially in environmental justice work. That gave me another push.

Even though I knew people were concerned about the issues, sometimes it does get discouraging when you don't get enough people participating. But the people came out of the woodwork for that. They saved up their strength for that moment to say ‘no more.’ I was so proud of that.”

Cochran credits REACT's work in garnering community support for the establish the Strategic Toxic Air Reduction program (STAR), which set more stringent limits on industrial pollution. They collected the signatures of over 3,000 community members through canvassing, community radio shows, community events and whatever ways they could reach people in impacted communities. They attended over 100 stakeholder meetings, made sure the hearing was well attended and engaged Louisville Metro Council on a regular basis over the course of the two years leading to its adoption.

“We reached out to so many different groups and individuals. We sent three speakers to many of the televised Metro Council meetings over the course of two years. This resulted in educating the public and Metro Council members, who eventually voted unanimously to support the STAR program. We engaged the NAACP and the teachers' union, both of which signed resolutions in support of the STAR program. We canvassed impacted neighborhoods and submitted over 3,000 signed postcards. The paper reported that it was the largest number of comments ever received by the district at that time. So I'd say the key to this is persistence.”

of

Data coupled with lived experiences

"We value integrity, and so we don't operate in hyperbole," Cochran says of REACT's approach. "The facts are horrible enough for us not to have to lie about what's happening to us. We don't exaggerate. We tell people what we know as we understand it. This is what it is, and we try our best not to speak on things that we don't know.

Because one thing about this work is – especially in the Black community, which has been plagued with other sorts of injustices – it's very, very easy to lose the trust of the community, and so you don't want to say things that are not true or that you don't know to be true.”

Cochran advises, “When you move outside of the scope of what you know, it gives industry and decision-makers the opportunity to invalidate your work and what you're doing.

Over the years, I can't remember there being any sort of [smear] campaign or ‘aha, we got you, REACT’ moment, because we only speak what we know, and what we know is built around the data and the lived experiences of people in our community. I think those are the things that lead people to trust the work that we do."

Drawing strength from her ancestors & hope for her children

When asked about what keeps her motivated through decades of challenging work, Cochran's answer reveals the deep well of inspiration she draws from.

"I am the daughter of Sterling Orlando Neal, Jr. and Emma Neal. Although they both have transitioned, they left me with so many examples of compassion for people around the world, love for the Black community, how to be loyal for good in the Black community, and how to fight for the Black community."

Beyond her parents, Cochran draws strength from a longer lineage of resistance.

"Some of my ancestors were literally tortured, split from their families, and traumatized, yet they resisted," she reflects. "On days that I feel so discouraged, I feel like giving up, I feel tired... I think about all of my ancestors who were under conditions I can't even imagine.

“They resisted through escape and revolts, among other things. Their self-determination was evident in their establishment of Black towns around this country. Their creativity was evidenced by all of the inventions that changed the world. They've merged their creativity and culture by using braided hair to create secret maps for escape from slavery. And so how could I not be motivated?”

Despite the slow pace of progress, Cochran maintains a profound hope for future generations.

"I'm hopeful for all of the future environmental justice warriors who I know will push forward in an even more effective manner than we're pushing forward," she says. "We're standing on the shoulders of folks who were fighting this fight. They moved the needle a little bit. We're trying to move it some more."

She pauses, then continues with conviction: "I'm hopeful for the day when our descendants will no longer have to fight against the greed and cruelty that creates injustice. I'm hopeful that one day our descendants will be able to rest without worry."

With a smile that conveys both wisdom and determination, she concludes: "I think it's going to happen, but it's not going to happen in my lifetime. But it brings me joy to know that it's going to happen.